Engineering is not equal to Science.

In December 2010 Henry Petroski, a professor at Duke wrote the following article in IEEE Spectrum (HERE).

Science is about understanding the origins, nature, and behavior of the universe and all it contains; engineering is about solving problems by rearranging the stuff of the world to make new things. Conflating these separate objectives leads to uninformed opinions, which in turn can delay or misdirect management, effort, and resources.

Tuesday, 30 August 2011

Saturday, 27 August 2011

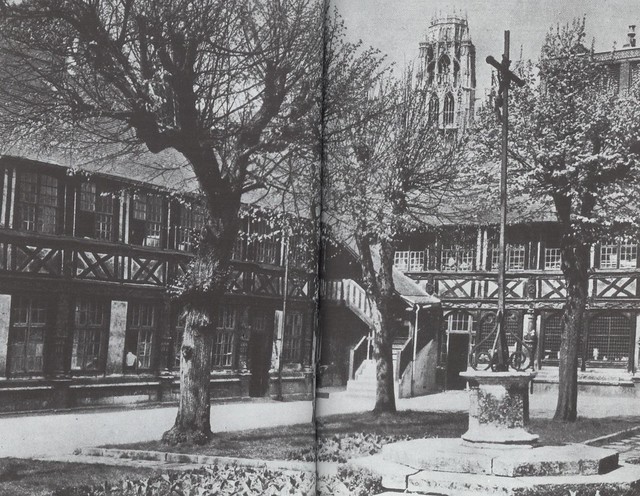

A Timeless way of Building

Christopher Alexander is an architect (links and details HERE).

One of his books is called A Timeless Way of Building. There is a Wikipedia entry on it HERE.

In this book Alexander sets out to describe the perfection of use to which buildings could aspire:

Alexander uses a concept which he calls the "quality without a name", and argues that we should seek to include this nameless quality in our buildings.

Also of note is the design of the book, it is a long series of italicized headlines that are followed by short sections that provide more detail. The author suggests that this long book (over 500 pages) can be read in an hour by only reading the italicised headlines, which frame the book's complete argument.

Alexander also published two follow on volumes on architecture that for a trilogy with this book - A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction and The Oregon Experiment.

The Pattern Language book has been very influential in computer science and software engineering (for example HERE).

One of his books is called A Timeless Way of Building. There is a Wikipedia entry on it HERE.

In this book Alexander sets out to describe the perfection of use to which buildings could aspire:

Alexander uses a concept which he calls the "quality without a name", and argues that we should seek to include this nameless quality in our buildings.

"The first place I think of when I try to tell someone about this quality is a corner of an English country garden where a peach tree grows against a wall. The wall runs east to west; the peach tree grows flat against the southern side. The sun shines on the tree and, as it warms the bricks behind the tree, the warm bricks themselves warm the peaches on the tree. It has a slightly dozy quality. The tree, carefully tied to grow flat against the wall; warming the bricks; the peaches growing in the sun; the wild grass growing around the roots of the tree, in the angle where the earth and roots and wall all meet.This quality is the most fundamental quality there is in anything."

Also of note is the design of the book, it is a long series of italicized headlines that are followed by short sections that provide more detail. The author suggests that this long book (over 500 pages) can be read in an hour by only reading the italicised headlines, which frame the book's complete argument.

Alexander also published two follow on volumes on architecture that for a trilogy with this book - A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction and The Oregon Experiment.

The Pattern Language book has been very influential in computer science and software engineering (for example HERE).

Wednesday, 17 August 2011

Mervyn Peakes Gormenghast

Here is an original page from one of Peakes' manuscripts for his Gormenghast trilogy, showing Fuchsia Groan and Steerpike.

And one of Steerpike.

And one of Steerpike.

Thursday, 28 July 2011

Rh Book Preface by James Watson

One of my great privileges was to get to know Ronnie Finn.

Professor Ronnie Finn FRCP (1930--2004)

Ronnie Finn received the Albert Lasker award (often known as the American Nobel prize in medicine) in 1980 for his contribution to the development of an effective treatment for Rhesus haemolytic disease. The resulting anti-Rh(D) injection, which is given to thousands of women worldwide every year, is estimated to have saved some half a million lives to date.

The book Rh; The Intimate History of a Disease and its Conquest by David R Zimmerman was published in 1973 it describes the history of this disease, first defined 40 years earlier and which is now preventable.

Here is the introduction to the book by James watson.

Professor Ronnie Finn FRCP (1930--2004)

Ronnie Finn received the Albert Lasker award (often known as the American Nobel prize in medicine) in 1980 for his contribution to the development of an effective treatment for Rhesus haemolytic disease. The resulting anti-Rh(D) injection, which is given to thousands of women worldwide every year, is estimated to have saved some half a million lives to date.

The book Rh; The Intimate History of a Disease and its Conquest by David R Zimmerman was published in 1973 it describes the history of this disease, first defined 40 years earlier and which is now preventable.

Here is the introduction to the book by James watson.

Friday, 22 July 2011

Friday, 15 July 2011

Wednesday, 13 July 2011

Friday, 8 July 2011

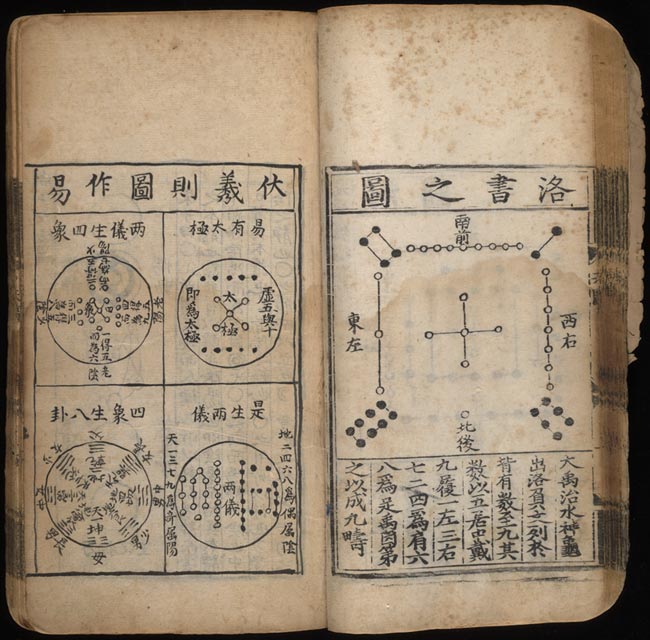

I Ching

Ancient Chinese Concept of Change

The Astronomical Phenomena. (Tien Yuan Fa Wei). Compiled by Bao Yunlong in the 13th century. Ming Dynasty edition, 1457-1463.

The book is an explanation of the 'Ba Gua' used in the Yi-ching (I Ching or Classic of Changes, also known as the Book of Divination). According to this Chinese world view, the universe is run by a single principle, the Tao, or Great Ultimate. This principle is divided into two opposite principles--yin and yang. All phenomena can be understood using yin-yang and five associated agents, which affect the movements of the stars, the workings of the body, the nature of foods, the qualities of music, the ethical qualities of humans, the progress of time, the operations of government, and even the nature of historical change.

Tuesday, 28 June 2011

Sunday, 26 June 2011

Art in the Field

Eugene Delacroix used art sketchbooks in much the same way as a field naturalist, or lab biochemist, would use a notebook. As a record of intense observation.

His sketchbooks from Morocco are particularly beautiful, they are vibrant and integrated sketches and notations.

A high resolution page is HERE.

His sketchbooks from Morocco are particularly beautiful, they are vibrant and integrated sketches and notations.

A high resolution page is HERE.

From a journal entry dated October 17, 1853:

“I began to make something tolerable of my African journey only when I had forgotten the trivial details and remembered nothing but the striking and poetic side of the subject. Up to that time, I had been haunted by that passion for accuracy that most people mistake for truth.”

Saturday, 25 June 2011

Friday, 24 June 2011

New Tube map for London

Here is a website with a new London tube map that tries to retain the clarity of the original London Underground map created by Harry Beck but incorporating more accurate geographical information. I must say I like it (for example I really like the depiction of the Thames - the Beck rendition misses the beautiful sweep and meander of this great river).

For example, I very regularly take the same route from Euston to Temple via Embankment. The old map tells you where you are within the London Underground Universe BUT not where you are within the Real-World Universe; is Temple North or South of Embankment? How far East is Temple from Euston?

A comparison is shown below.

Tuesday, 21 June 2011

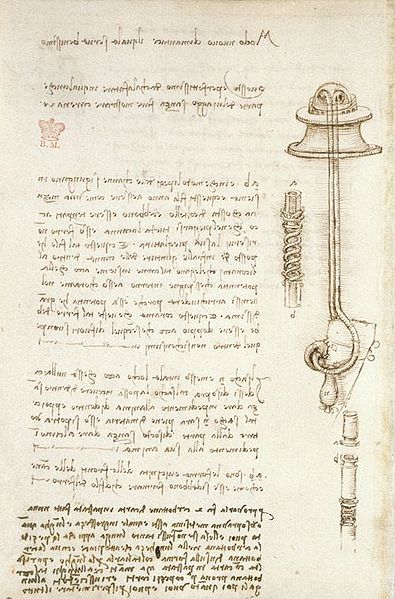

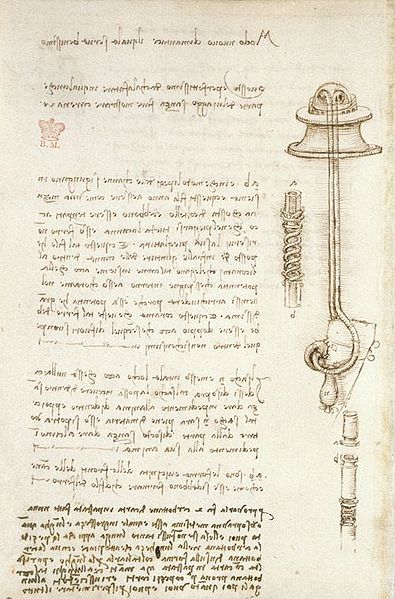

The da Vinci Principle

If all human understanding about how to make deep and insightful observations in art and science were to be lost, and only one statement about how best to observe the world was preserved, the sentence that would contain the most information in the fewest words would be; Above all else, keep a notebook.

This should probably be called the da Vinci principle, after that most famous observer Leonardo da Vinci (1452--1519). Leonardo has left us only about 15 paintings, but in excess of 13,000 pages of notes and drawings. Leonardo was nothing, if not a note taker.

This should probably be called the da Vinci principle, after that most famous observer Leonardo da Vinci (1452--1519). Leonardo has left us only about 15 paintings, but in excess of 13,000 pages of notes and drawings. Leonardo was nothing, if not a note taker.

Sunday, 19 June 2011

The palest ink is better than the sharpest memory

It's interesting that in both lab based chemistry and field based natural science there is an obsession about making contemporaneous observations; in ink, in a bound notebook, with diagrams.

In natural history the method that is still used is that developed by Joseph Grinell.

In natural history the method that is still used is that developed by Joseph Grinell.

A very cool Father s Day present...

Had a really great Fathers day. The weather cleared up, I spent time in the garden and got some lovely presents.

One of the presents that I will take time over is a highly visual book called "Field Notes on Science & Nature" edited by Michael Canfield.

One of the presents that I will take time over is a highly visual book called "Field Notes on Science & Nature" edited by Michael Canfield.

"Once in a great while, as the New York Times noted recently, a naturalist writes a book that changes the way people look at the living world. John James Audubon's Birds of America, published in 1838, was one. Roger Tory Peterson's 1934 Field Guide to the Birds was another. How does such insight into nature develop? Pioneering a new niche in the study of plants and animals in their native habitat, Field Notes on Science and Nature allows readers to peer over the shoulders and into the notebooks of a dozen eminent field workers, to study firsthand their observational methods, materials, and fleeting impressions. What did George Schaller note when studying the lions of the Serengeti? What lists did Kenn Kaufman keep during his 1973 "big year"? How does Piotr Naskrecki use relational databases and electronic field notes? In what way is Bernd Heinrich's approach "truly Thoreauvian," in E. O. Wilson's view? Recording observations in the field is an indispensable scientific skill, but researchers are not generally willing to share their personal records with others. Here, for the first time, are reproductions of actual pages from notebooks. And in essays abounding with fascinating anecdotes, the authors reflect on the contexts in which the notes were taken. Covering disciplines as diverse as ornithology, entomology, ecology, paleontology, anthropology, botany, and animal behavior, Field Notes offers specific examples that professional naturalists can emulate to fine-tune their own field methods, along with practical advice that amateur naturalists and students can use to document their adventures."

Its from Harvard University Press (site here).

This book is a fantastic resource for anyone interested in how field scientists use the simplest of tools; often just a pencil and notebook, to create deep insight.

“There is no other book like this--one that takes readers out of the laboratory and into the field to learn the basics of natural history and the fun of observing nature.”

—George Schaller

Some spreads and illustrations below.

Saturday, 18 June 2011

Truth is Stranger than (Science) Fiction

Here is a piece about physicists hacking into what was thought to be an "unbreakable" quantum approach to cryptography. Forget the science - look at the piece of kit that they used to hack in with!

Thursday, 16 June 2011

Great Home-workers of our Time

I have been inspired recently by two eminent scholars who have famously spent as much of their time working at home either in seclusion or with their family.

Liam Hudson (1933-2005)

"He wrote presciently in 1977, in a talk for an international conference Creating the Productive Workplace, that the Nobel prizewinner Robert Stone “had the good sense to work at home with his wife” — he said that he always felt most at ease in his own home."

From his Obituary in the Times, HERE

Richard Stone (1913- 1991) - 1984 Nobel prize in Economics.

"In 1980, I retired from my university post. My retirement, however, has not severed my links with the two colleges with which I have been associated throughout my life in Cambridge: King's College, where I have held a Fellowship since 1945, and Gonville and Caius College, where I spent my undergraduate days and where I have been an Honorary Fellow since 1976. Nor has it altered my habits much except in so far as it has enabled me to work full time where I have always preferred to work at home."

From his Autobiography HERE.

Escher or Bust

Here is a paper by artist/computer scientist San Le that describes how to create artistic tesselations, including some that Escher could never have - as they are based on Penrose tilings.

Wednesday, 15 June 2011

Data Wrangler

Stanford Vis Lab have a great tool for interactive and intelligent data transforms called Data Wrangler.

Tuesday, 7 June 2011

Drawn In

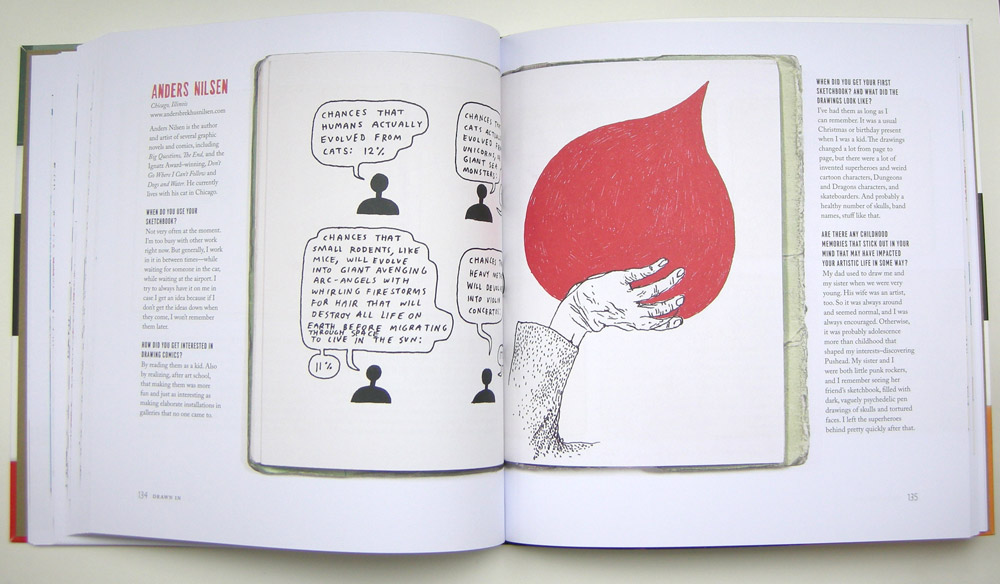

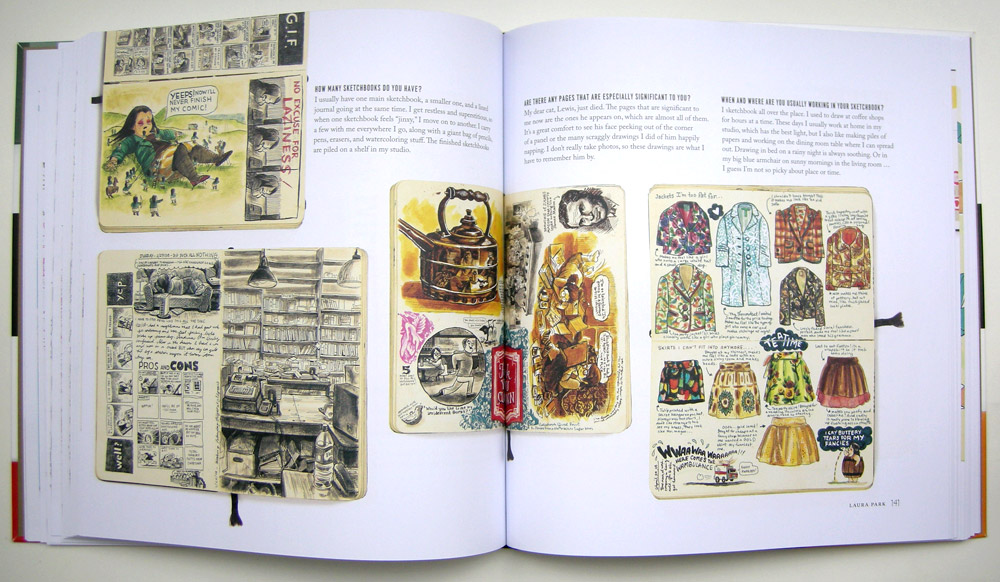

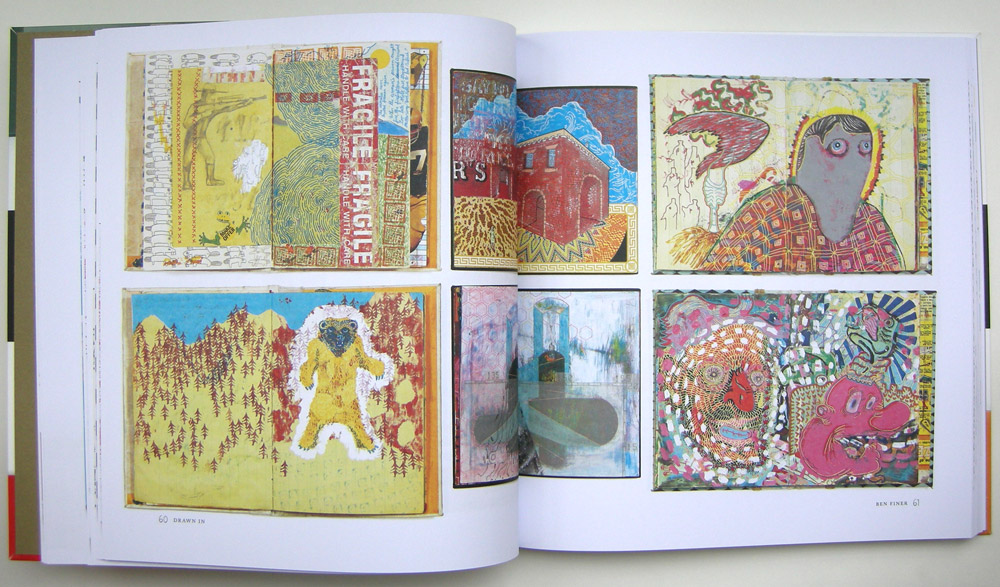

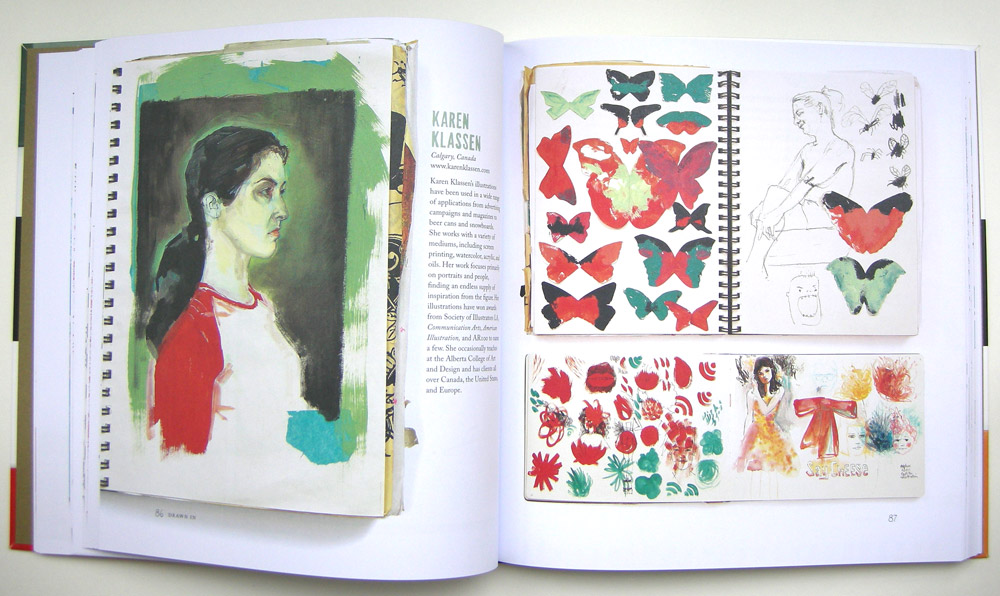

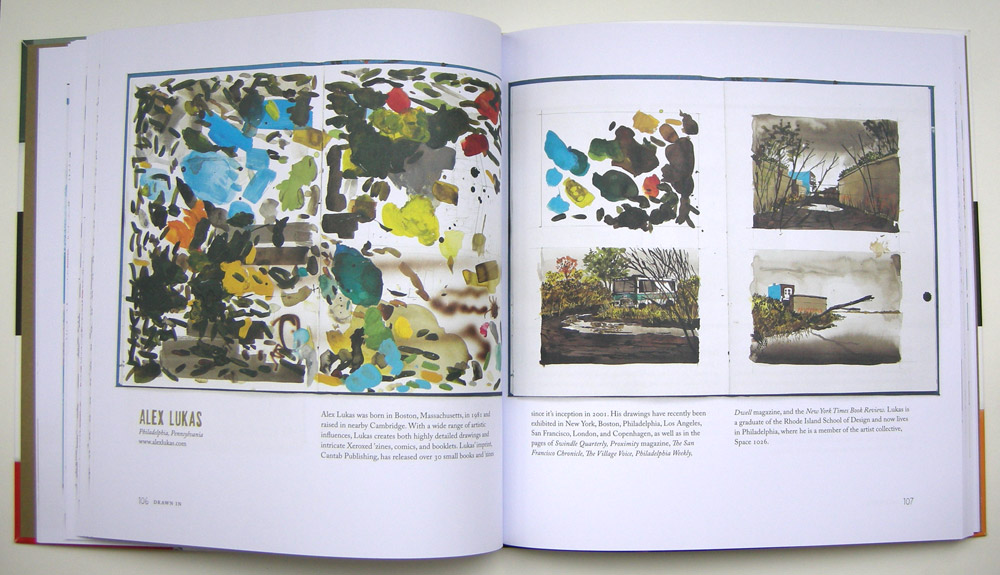

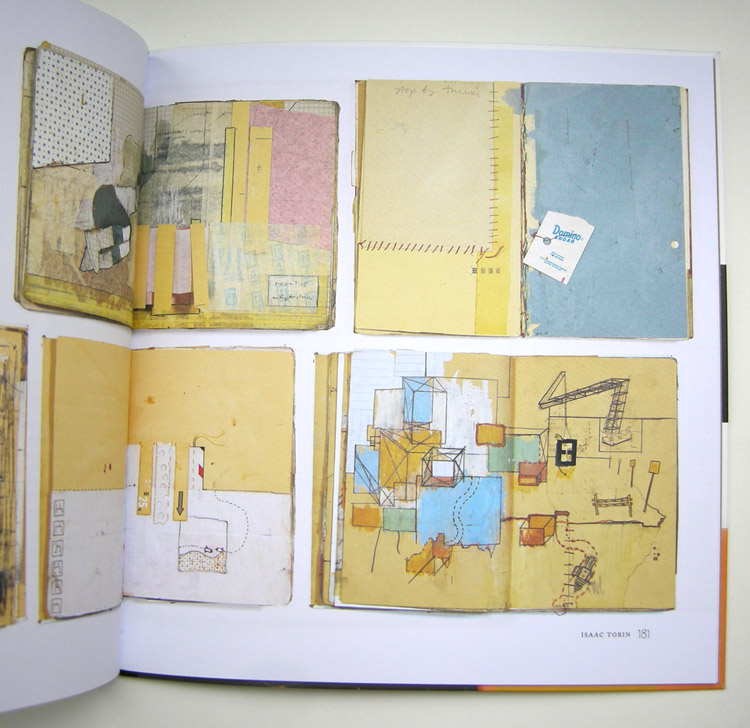

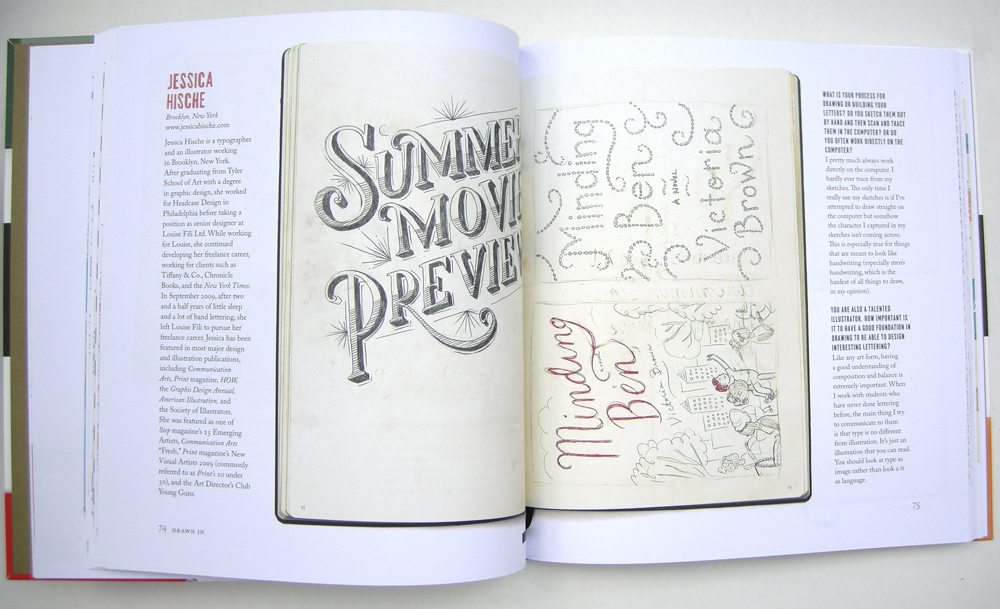

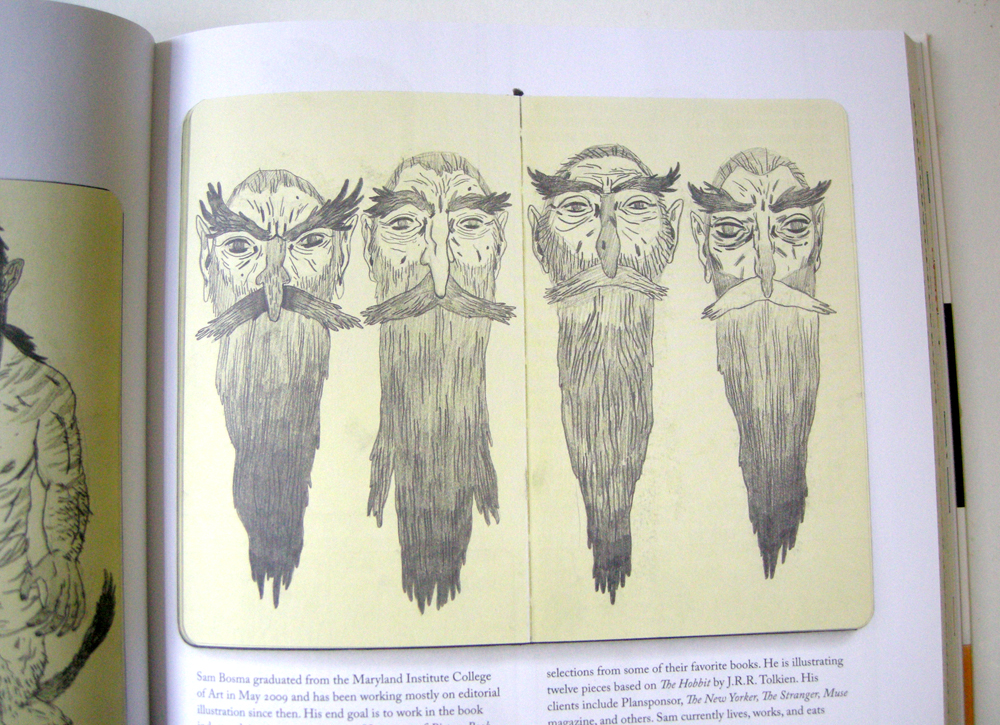

Drawn In: A Peek into the Inspiring Sketchbooks of 44 Fine Artists, Illustrators, Graphic Designers, and Cartoonists.

by Julia Rothman.

Blurb:

People are fascinated by artist's sketchbooks. They offer a glimpse into private pages where artists brainstorm, doodle, develop and work on ideas, and keep track of their musings. Artists use these journals to document their daily lives, produce their initial ideas for bigger projects, and practice their skills. Using a variety of media from paint to pencil to collage, these pages can become works of art themselves. They often feel fresh and alive because they are first thoughts and often not reworked. These pages capture the artist's personalities along with glimpses of their process of working and inspirations.

See inside the sketchbooks of artists Jessica Hische, Mike Perry, Jen Corace, Matt Leines, Jill Bliss, Camilla Engman, Anders Nilsen and many more.

See inside the sketchbooks of artists Jessica Hische, Mike Perry, Jen Corace, Matt Leines, Jill Bliss, Camilla Engman, Anders Nilsen and many more.

Sunday, 5 June 2011

Friday, 3 June 2011

Sunday, 29 May 2011

Family History

My Dad's Dad worked at the Ogdens tobacco factory in Liverpool, here is a Cigarette card from Ogdens.

Moxon and Francis Bacon

Joseph Moxon's fame rests largely on his two volumes of Mechanick Exercises. These tracts were printed originally as 14 separate pamphlets after which they were collected and reprinted. Moxon's Mechanick Exercises was written and published to give it's readers basic instructions in all of the chief trades of his day. Between 1677 and 1680 Moxon published fourteen of these exercises; including smithying, joining, carpentry and related arts. This book was the first book in England to be published in parts, or fascicules.

That Geometry, Astronomy, Perspective, Musick, Navigation, Archtecture, etc are excellent Sciences, all that know but their very Names will confess: yet to what purpose would geometry serve, were it not to contrive Rules for Hand-Works? Or how could Astronomy be known to any perfection, but by instruments made by Hand? What Perspective should we have to delight our Sight? What Musick to ravish our Ears? What Navigation to Guard and Enrich our Country? Or what Architecture to defend us from the inconvenience of different weather, without Manual Operations?

The American engineer Eugene Ferguson (1916--2004) has made a compelling argument that engineers and other technologists have habitually used visual and other non-verbal thinking since the Renaissance. [Ferguson, E. (1994). Engineering and the Mind's Eye. MIT Press.] Engineers actively engaged in the creative process of design use deeply visual means to develop, share and modify their ideas. Ferguson has traced over the past five centuries the parallel history of textual descriptions and their often interdependent visual descriptions. Furthermore, Ferguson argues that these visual representations are not accidental, they are a fundamental facet of the way an engineers mind's eye works;

The mind's eye, the locus of our images of remembered reality and imagined contrivance, is an organ of incredible capacity and subtlety. Collecting and interpreting much more than the information (entering the optical eyes), the mind's eye is an organ in which a lifetime of sensory information (in all its forms) -- is stored, interconnected and interrelated.

One example used by Ferguson to illustrate the development of the Mind's Eye, is the movement of scientists who were inspired by the philosopy and scientific method of Francis Bacon -- both his Novum Organum a philosophical work in Latin published in 1620 and his utopian novel {New Atlantis, published in English in 1627. Bacons' grand scheme was to enhance the power and greatness of man through the application of new science. One of the components of this project was what Bacon called the natural histories of trades; detailed descriptions of the technical information that had been kept secret in the trade guilds and workshops for hundreds of years. Bacon thought that by making public the details of the tools, techniques and processes used in the crafts it would lead to an improvement of this practical knowledge by scholars and also general progress derived from the development and application of this technical knowledge.

In spite of a number of serious attempts, the Royal Society itself never did publish the series of natural histories of trades envisioned by Bacon. The fellows of the Royal Society were, by and large, educated gentlemen with little or no connection to the practical goings-on of the workshops in which the ancient crafts and arts were actually practiced. Even if they had been better connected the secrets of the trades were deliberately obscured by the master craftsmen to protect their livelihoods. So in spite of Francis Bacons' impetus and the good intentions of some of the founders of the Royal Society, in fact it was left to a single man, Joseph Moxon, to do what `a whole variety of well-meaning gentlemen could not'. [Preface by B. Forman and C. F. Montgomery, Eds. Joseph Moxon (1703). Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handy-Works. Praeger, New York, 1970.]

Joseph Moxon began sharing the arcane knowledge of Handy-works he had gained by writing and publishing and in this endeavour was directly inspired by Bacon. In the preface to volume one he says;

The Lord Bacon in his `Natural History' reckons that philosophy would be improved by having the secrets of all trades lye open; not only because much experimental philosophy is caught among them, but also that the trades themselves might by a philosopher be improved.

Moxon was well placed to meet the challenge posed by Bacon, in this context David Pankow notes; `... the pioneers of manufacturing technology and scientific inquiry were prying away at the rotting doors of medieval trade secrecy.' [Pankow, D. (2005). The Printers Manual. An Illustrated History. RIT Cary Graphics Arts Press. Rochester, New York.]

Whereas today it is possibe to argue that the global economy is converging on a single, highly interconnected, knowledge economy, the knowledge economies of previous era's were much more localised and in some cases they can be identified with small groups of gifted, industrious and like minded individuals. For example, the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, now known almost universally as The Royal Society, which was founded in London in November 1660, can be thought of as an early, and rather localised, example of a knowledge economy.

Historically, the Royal Society has always emphasised the importance of openly disseminating new scientific knowledge via books and periodicals; it has been publishing Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society since March 1665 which makes it the longest-running scientific journal in the world. Also in 1665 it began publishing significant scientific books, the first being Robert Hooke's incredible visual monograph, Micrographia.

Running in parallel with the official early publications of the Royal Society, there is a collection of periodicals and books from this period that were published by a little known fellow of the Royal Society, Joseph Moxon (1627-1691), at his own expense and under his own imprint the sign of the Atlas, variously located in Ludgate Hill and Cornhill in London.

But Joseph Moxon was not simply a printer of technical books. In spite of his puritanical and rather humble background he was appointed Royal Hydrographer to King Charles II in January 1662, a position in which Moxon was responsible for maintaining official charts of ocean navigation routes. In addition, as a consequence of being on good personal terms with dozens of the founding scientific members of the Royal Society, he was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society in 1678. Unlike most of the early fellows of the Royal Society, Joseph Moxon himself was neither a gentleman nor a scientist. He wrote, printed and sold books on mechanics, the printing trades, geometry, mathematics and perspective, he typeset and published books full of logarithm tables and he designed and built celestial and terrestrial globes and printed and published books of maps and sea-plats.

Looking back from a vantage point nearly 400 years later, it is difficult to understand Moxon's output as a coherent body of work. His translations and original works, as well as his globes and maps, appear to be a random collection of items that would be of interest to a typical scientific gentleman of the Royal Society. But this characterisation would be an injustice to Joseph Moxon. Although he certainly was not a gentleman scientist, he had an important role to play in the knowledge economy of restoration England. He was an early example of a highly visual and entrepreneurial technologist, who not only made a good living from the practical application of scientific knowledge, but also had a real desire to open up the secrets of the craft guilds of his time, so that other people could learn and apply the type of knowledge he had acquired himself.

Saturday, 28 May 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)